China

India seeks to overtake China as the fastest growing economy in the world

Published

4 years agoon

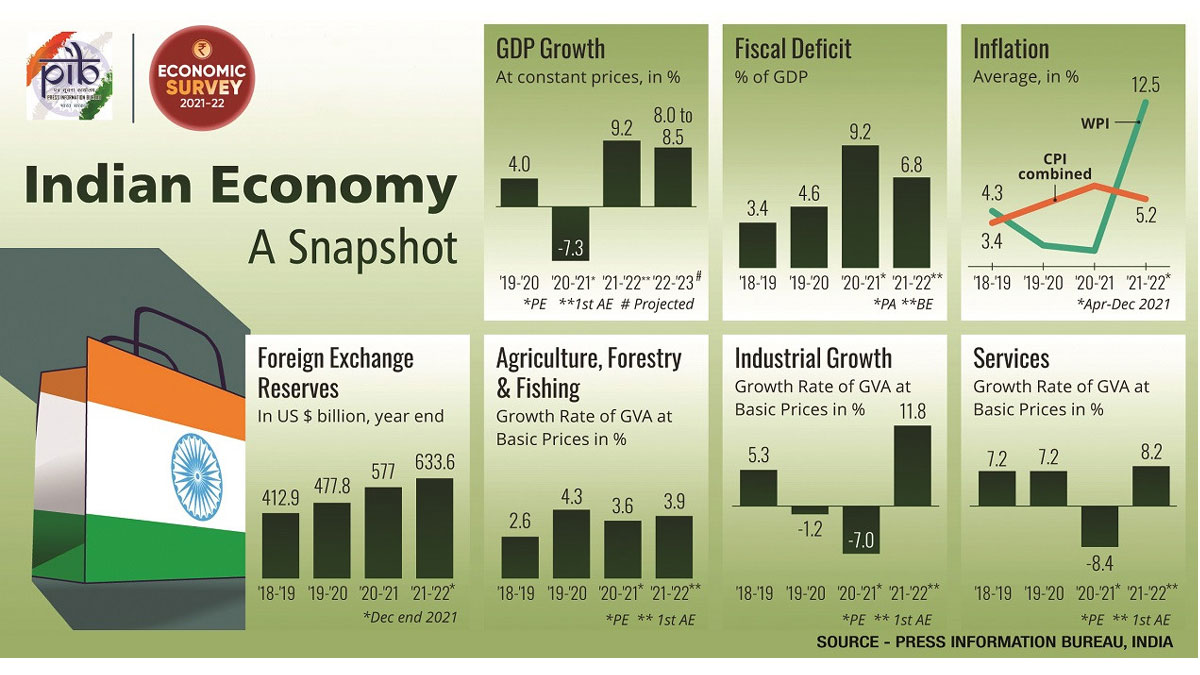

India is going to step up spending to $529.7 billion in the 2022-23 fiscal year to build public infrastructure and drive economic growth to 8-8.5%, as it looks to dethrone China as the fastest growing economy.

Indian Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, while presenting the annual budget on Tuesday, said total government spending in FY23, beginning in April, will be 4.6% more than the current 2021-22 fiscal year.

But inflation poses a major risk for the country in achieving the targeted economic growth rate, according to an economic survey tabled by Sitharaman just a day ago.

There is a threat of imported inflation from the depreciating rupee value against the US dollar and the rising global oil prices that have touched $90 a barrel last week, the survey found.

“Although the high wholesale price index inflation is partly due to base effects and will even out, India does need to be wary of imported inflation, especially from elevated global energy prices,” the survey reads.

The consumer price index (CPI) or retail inflation shot up to 5.59% in December last year from 4.91% in November.

What does high inflation in India mean for Bangladesh?

Zahid Hussain, former lead economist at the World Bank Bangladesh office, said that even before this year’s proposed budget, India’s rising inflation was identified as one of the biggest challenges behind the country’s rapid economic growth.

“I think this inflation will continue even in the third wave of the ongoing coronavirus in the country. And if that happens, it will affect our economy as well. In particular, our import costs may increase slightly,” Hussain warned.

“Our business and economic ties with India are very old. Moreover, the import-export relationship between the two countries is quite strong. Especially our imports from India have been increasing for the last few years,” he told media.

“A recent Policy Times report predicted that Bangladesh would be the fourth largest export destination for India in the current FY22. So, Bangladesh is becoming important for them day by day. However, if this picture of import is different for us, the open market will remain,” the economist also said.

Shahidullah Azim, vice-president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), said that Bangladesh imports yarn, fabric, cotton, and some other apparel-related raw materials from India.

“If the inflation rate rises in India, it will have an impact on the overall economic activity of the country. So naturally, there is a strong possibility that the prices of the products we import will go up,” he added.

However, he said, in this global free-market economy, there is no chance of being dependent on any particular country for both export and import.

“If the prices of Indian products go up, we have to find another market to meet our import demand,” he added.

He also said that there are many countries in the world that export RMG related raw materials.

“If the prices go out of our reach, then we have to rush to those countries to find new import sources,” he added.

A director of Savar-based Aboni Fashions Limited also said their factory imports a major portion of yarn and fabric from India.

“Being a neighbouring country, it is quite convenient to import raw materials from India as it saves costs and lead time,” he added.

But if the price of apparel-related raw materials increases due to inflation, it is natural to look for a new market, he added.

In the first seven months of the current fiscal year (April-October of 2021), Bangladesh’s imports from India increased by 81% over the same period of the previous fiscal year, amounting to approximately $7.7 billion.

Spending spree to boost growth in FY23

India will allocate trillions of rupees to expressways, affordable housing and solar manufacturing to put growth on a firmer footing in FY23, the Indian finance minister said while presenting the budget on Tuesday.

Sitharaman said public investment must continue to take the lead and pump prime private investment and demand.

“The economy has shown strong resilience to come out of the effects of the pandemic with high growth. However, we need to sustain that level to make up for the setback of 2020-21,” she said.

She announced spending of $2.68 billion for a highway expansion programme and said 400 new trains would be manufactured over the next three years, reports Reuters.

The fiscal deficit for the current year would be 6.9% of the GDP, slightly more than the 6.8% targeted earlier, the finance minister also said.

For the next fiscal year, the Modi government is targeting a deficit of 6.4% of GDP, hoping to build on higher tax revenues and privatisation of state firms.

Abheek Barua, chief economist of HDFC Bank, told Reuters that the 2022-23 budget finely balanced fiscal retreat with supporting economic recovery.

“It focused on a familiar strategy of driving capital expenditure to drive growth, with the intention of crowding in private investment through higher public spending. Although markets could be disappointed with a higher fiscal deficit of 6.4% of GDP for FY23 than expected, it is perhaps prudent to not undertake aggressive fiscal consolidation at this nascent stage of recovery,” he added.

Christian de Guzman, senior vice president at Moody’s Investors Service, said: “Despite the higher-than-expected growth, we still saw a fiscal deficit that was wider than what was budgeted. That continues to demonstrate the risks that are still ongoing from the pandemic.”

Sitharaman also said the central bank would introduce a digital currency in the next fiscal year using blockchain and other supporting technology.

But India’s central bank has voiced “serious concerns” around private cryptocurrencies on the grounds that these may cause financial instability.

Financial aid for neighbours, Tk345 crore for Bangladesh

Meanwhile, India has also announced a Rs300 crore (approximately Tk345 crore) annual budgetary financial assistance for Bangladesh in FY23, up from the Rs200 crore (Tk230 crore) in the current fiscal year.

It has also allocated Rs200 crore as aid to Taliban-ruled Afghanistan and Rs600 crore to military-run Myanmar.

Nepal will get Rs750 crore as foreign aid from India, the Maldives will get Rs360 crore, Bhutan will get Rs2,266.24 crore, and Mauritius will get Rs900 crore.

You may like

-

China’s ZTE on NBR radar

-

Why India is silent on US interference in Bangladesh

-

2 top officials from US, India arrive in Dhaka today

-

Pelosi to visit Taiwan despite China warning military action

-

Bangladesh, India share visions of connecting South, Southeast Asia

-

India to launch state-backed ‘digital rupee’, tax crypto

China’s Ant Group said on Saturday that its founder Jack Ma will no longer control the Chinese fintech giant after the firm’s shareholders agreed to implement a series of shareholding adjustments that will see him give up most of his voting rights.

Ma previously possessed more than 50% of voting rights at Ant but the changes will mean that his share falls to 6.2%, according to Reuters calculations.

While Ma only owns a 10% stake in Ant, an affiliate of e-commerce giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd (9988.HK), he exercised control over the company through related entities, according to Ant’s IPO prospectus filed with the exchanges in 2020.

Hangzhou Yunbo, an investment vehicle for Ma, had control over two other entities that own a combined 50.5% stake of Ant, the prospectus showed.

China

Taiwan reports new large-scale Chinese air force incursion

Published

4 years agoon

January 23, 2022

TAIPEI, Jan 23 (Reuters) – Taiwan on Sunday reported the largest incursion since October by China’s air force in its air defence zone, with the island’s defence ministry saying Taiwanese fighters scrambled to warn away 39 aircraft in the latest uptick in tensions.

China

In Asia China’s long game beats America’s short game

Published

4 years agoon

December 12, 2021

Submarines are stealthy, but trade is stealthier. Both generate security—the former by deterrence, the latter by interdependence. But the kind of security created by trade lasts longer.

Submarine deals are easy to walk away from. Just ask France, which this year lost a long-standing contract to provide attack submarines to Australia. Economic interdependence created by trade deals is harder to unravel. Just ask Trump, who couldn’t break up the North American Free Trade Agreement and had to settle for a cosmetically renegotiated pact.

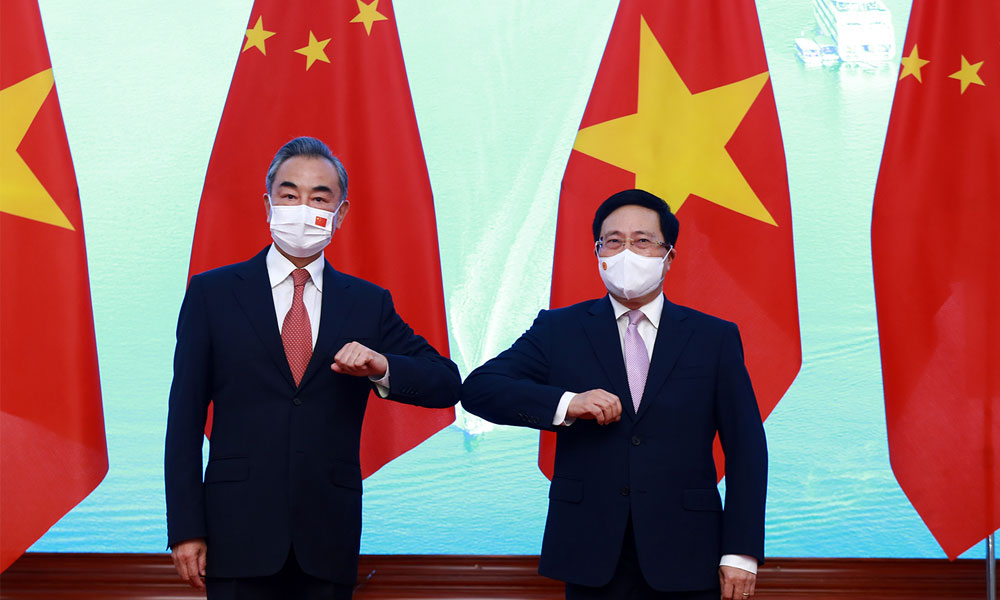

This contrast highlights the difference between the short-term game Washington is playing in the Indo-Pacific and the long-term one played by Beijing. The United States is betting on the AUKUS security pact it signed with Australia and the United Kingdom, the main feature of which is a promise to deliver submarines to Australia. China is betting on using trade to win over its neighbors, particularly the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the most successful Asian bloc.

Washington is right on one point. Superficially, the three AUKUS members have strong connections and largely see eye to eye. ASEAN, on the other hand, looks like a ramshackle outfit barely able to manage errant member states such as Myanmar. The bloc is also struggling to generate a coherent regional response to the growing U.S.-China rivalry. Nor can it calm the troubled waters of the South China Sea. But if ASEAN is too weak to impose its will on its own members, let alone on others, that unimposing weakness is also its strength, allowing the bloc to build trust in the region and beyond.

I first attended an ASEAN meeting as a Singaporean official exactly 50 years ago, in 1971. As soon as I walked into the conference room, I could smell the thick clouds of distrust among the five founding members. Two decades later, when I attended similar ASEAN meetings as the senior official from Singapore, the clouds of distrust had disappeared. Instead, the Indonesian culture of musyawarah and mufakat—consultations and consensus—had infected ASEAN. Gradually, this culture of consultations and consensus generated geopolitical miracles, some so stealthy that few outside the region have noticed them.

Washington can focus on selling submarines to Australia—or cross the Rubicon and sign free trade agreements with East and Southeast Asia.

Following the end of the Vietnam War, during which ASEAN supported the United States, hostility and distrust between Vietnam and ASEAN were palpable. But when the Cold War ended, ASEAN integrated Vietnam into the region’s economy, helping the country emerge as another East Asian economic miracle. The most important lesson Vietnam learned from ASEAN was to trade even with one’s adversaries, just like the original members of ASEAN overcame their distrust of one another through trade. That’s why trade between India and Pakistan only tripled from 1991 to 2021, while trade between Vietnam and China—which had fought a war against each other in 1979—grew 6,000 times over. In short, ASEAN’s culture generated peace and prosperity.

Another major ASEAN breakthrough was to generate greater economic engagement between Japan and South Korea. Although the two countries are both U.S. allies, Washington can barely persuade them to talk to each other. Indeed, in recent years, there was neither consultation nor consensus between Seoul and Tokyo. And yet, despite this, ASEAN has persuaded the two East Asian neighbors to sign a free trade agreement among themselves (and with China too): the ASEAN-initiated Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), signed in 2020 by the ten ASEAN member states, Australia, New Zealand, China, Japan, and South Korea. Indeed, the economic integration of the powerful Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean economies will generate most of the RCEP’s economic boost. It was ASEAN that accomplished this little-noticed miracle.

Here’s a simple word test Washington should carry out. Count which words appears more in the speeches of U.S. President Joe Biden, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, U.S. Secretary of Defense Llloyd Austin, and White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan (the four custodians of the United States’ Indo-Pacific policies): ASEAN and the names of its member states, or Australia.

The answer will be Australia. Washington’s affection for Australia is genuine and its concern heartfelt, which goes a long way toward explaining AUKUS. Yet geopolitics is also a cruel business, where emotions create a competitive disadvantage. If Beijing focuses on ASEAN and the RCEP and Washington focuses on Australia and AUKUS, Beijing will win.

Here’s why. The big game is economic, not military. In 2000, total U.S. trade with ASEAN was $135 billion, more than three times China’s trade of $40 billion. By 2020, China’s trade of $685 billion was almost double the United States’ trade of $362 billion. Washington still sees Japan as an economic superpower. And in 2000, Japan’s economy was eight times larger than ASEAN’s. But by 2020, it was only 1.5 times larger. By 2030, Japan’s economy will be smaller than ASEAN’s.

China’s engagement with ASEAN is deep and broad. High speed railways are being built by China in Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand. Amazingly, despite the patent distrust between Hanoi and Beijing, the metro system in Hanoi is being built by China too. And when Southeast Asia was looking for vaccines, Chinese vaccines came first. Indonesian President Joko Widodo, a key regional leader, was happily vaccinated with Chinese vaccines. There’s no doubt that relations between China and several ASEAN states are complicated and face challenges. Yet the range and depth of cooperative endeavors cannot be denied.

And economic ties will grow stronger as the economic miracle growth story of ASEAN is just beginning. Many of the regional economies are at the tipping point of becoming middle-class societies. Australia has 25 million in its middle class. ASEAN will soon have several hundred million. Here’s a leading indicator: In 2020, ASEAN’s digital economy valued around $170 billion. By 2030, it could reach $1 trillion. This massive explosion of the region’s digital economy will in turn generate new webs of interdependence, strengthening even more the massive ecosystem of interdependence developing in the region.

So, ultimately, this is the strategic choice Washington must face. Focus on selling submarines to Australia—or cross the Rubicon and sign free trade agreements with East and Southeast Asia. And here’s the real kicker: At the end of the day, the Trans-Pacific Partnership was essentially a product of Washington’s talented negotiators, who produced a truly blue-chip trade agreement. After the United States withdrew from the agreement in 2017, the revised Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership remained modeled on the original. But the United States cannot even dream of the possibility of rejoining it; by contrast, China has applied to join.

The final question is this: Can Washington reenter Asia’s great economic game? Yes, it can. It still has some assets. Even though China trades far more with ASEAN, U.S. private investment in ASEAN dwarfs that of China. The total stock of U.S.-held foreign direct investment in ASEAN was about $318 billion in 2019; Chinese investment accounted for only about $110 billion. Given the explosive growth potential of the ASEAN region, Washington should find creative ways of driving even more U.S. investment in ASEAN, taking advantage of the huge reservoirs of goodwill toward the United States that still exist in the region.

In short, don’t focus on selling submarines. Focus on encouraging U.S. investment and trade in the Indo-Pacific. It’s the economy, stupid.

Kishore Mahbubani, a distinguished fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute, is the author of Has China Won? The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy. Twitter: @mahbubani_k

Disclaimer: This article first appeared on Foreign Policy, and is published by special syndication arrangement

From Confusion to Clarity: Dheow’s Book Helps Users Master ChatGPT Conversations

Pre-Orders Open for Mojahidul Islam’s Latest Computer Book ‘AI Shikhun, Taka Gunun’

Bangladesh’s Press at a Crossroads: Between Promises of Reform and the Shadows of Repression